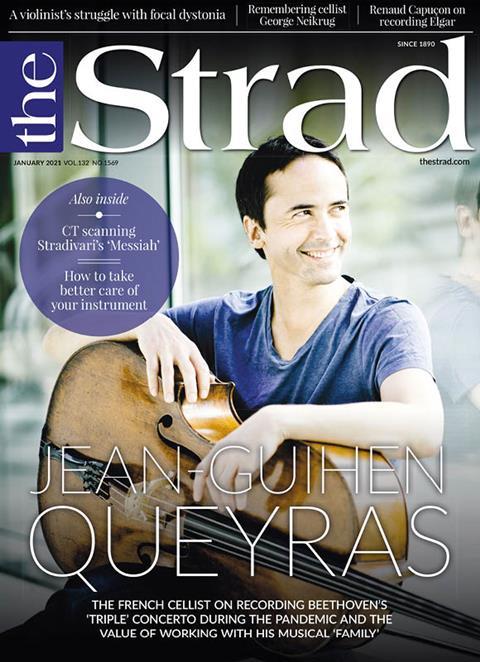

Recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto last June allowed French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras to step back into near normality, among colleagues and friends. He tells Pauline Harding about recording at a social distance, the importance of musical ‘family’, and why working with living composers has helped him to nd contemporary relevance in music from every era

Photo Peter Meisel/BR Symphony Orchestra

Queyras performs Schumann with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Eliot Gardiner in 2017

Reading the programme notes for a concert at London’s Wigmore Hall come from a speaker, ringing out over an empty stage, is somehow an other-worldly experience. The date is 24 September 2020 and this is one of the first live concerts to take place at Wigmore after months of national lockdown. For those of us unable to make the physical journey to the hall, its online live stream has at least enabled us to be present in some respect. Even watching the setting remotely, on screen, brings with it a ghostly sense of a familiar past played out within a surreal present. Audience eyes glint above bluish surgical masks spaced out in small groups across the 552-seat hall, and even the bouquets of pink flowers that frame the stage seem like a nostalgic gateway back into a far and distant time. Between them, the performance space bathes in golden light, beneath a robotic claw of microphones.

Jean-Guihen Queyras looks small and isolated when he enters the stage, ready to begin his lonely musical journey through some powerful 20th-century solo repertoire. The scene brings our recent conversation back to my mind. ‘Music is interaction par excellence,’ the French cellist told me a few weeks earlier. ‘It has been such a huge shock to be apart.’ And yet when he coaxes the opening drone of Saygun’s Partita for solo cello (1955) from his C string, the stage blossoms with new life. He is suddenly in company, as he weaves Turkish folk scenes, characters and voices with his bow, in full command both of sound and of silence. His eyes are closed and he seems to have flown far into an alternate reality, away from his masked listeners. In Britten’s Third Cello Suite (1971) and Kodály’s Sonata for solo cello op.8 (1915), he is by turns neurotic, defiant, determined, mournful and accepting, pulling the world around him into the one that he creates. His bow travels from the bridge to well up over the fingerboard; his pizzicato takes his right hand all the way down the fingerboard to the bridge. His posture is often skewed, with his left foot tucked slightly under his seat, his right stretched out before him. Convention falls secondary to the response of his cello, which he plays with absolute understanding and unthinking naturality.

Photo: Philipp Seliger

In concert with violinist Daniel Sepec and violist Tabea Zimmermann in August 2020 at the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg

Queyras’s performance approach, he tells me, is firmly rooted in his early musical education. His childhood teacher in Provence, Claire Rabier, insisted that music was for sharing and connecting, and as a teenager he was taught by Reine Flachot, who gave him a grounding in French technique coupled with the flexibility of a strong technical imagination. It was then Timothy Eddy in New York, he says, who ‘taught me how to speak through the tools that we have, to express all the subtleties of language and psychology – of what you feel in a moment. You hear a sound, you listen to it in the room, and then you make it live with the time and the place where you are playing it. That, to me, is why we make music.’

Boulez’s Ensemble Intercontemporain perhaps gave him the greatest insights into how to bring a score alive. He joined the Paris-based group when he was 23 – in part to satiate the desire for a musical ‘family’ instilled in him during his childhood lessons in Provence – and over the next decade discovered a whole new universe, even recording Ligeti’s Cello Concerto and Boulez’s own Messagesquisse (with the Ensemble de Violoncelles de Paris) under the baton of the then-living legend. ‘I had this extraordinary experience of working on a day-to-day basis with composers from all over the world,’ says Queyras. ‘Ligeti, Berio, Helmut Lachenmann, but also young composers who were not known at all. I had always been excited about contemporary music – about getting these crazy signs on a piece of paper where you have no idea how it will sound, and then you try to play it and see what comes out of your cello. Asking the composers, “What do you want exactly?” has had an enormous influence on the way I look at a score and try to bring it to life.’

Photo: Holger Talinski/Atelier Lyrique

Performing solo cello works by Bach, Saygun and Kodály at the opening of Atelier Lyrique de Tourcoing in France in September 2020

Although he has long since left the French ensemble, Queyras’s sense of musical family continues to shape his career today. In 2002, he united with violinists Antje Weithaas and Daniel Sepec and violist Tabea Zimmermann to found the Arcanto Quartet; and since his early thirties he has been a devoted cello professor – currently at his alma mater the Freiburg University of Music. Other ‘family members’ include pianists Alexandre Tharaud and Alexander Melnikov, and violinist Isabelle Faust. ‘Everything that has happened in my life as a musician is because I meet people,’ says Queyras. ‘Meeting Isabelle was significant; meeting Pierre Boulez, and also Tabea, changed my life.’

Over the past few years, he and Faust have recorded Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (released 2020), Beethoven duos and piano trios with Melnikov (re-released as a box set in 2020), and the Schumann Piano Trios (2015–16), also with Melnikov, all for Harmonia Mundi. The third Schumann disc includes Queyras playing the Cello Concerto with the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra and conductor Pablo Heras-Casado. Queyras’s relationship with this orchestra goes back to his student days: ‘It was actually founded by students at the Freiburg University of Music when I was studying there, so I met a lot of them when I was 17, 18 years old, and we go back a really long way!’

Queyras, Faust, Melnikov and the Freiburg orchestra release their latest recording, of Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto, in February. Work took place during two intense days at the Teldex Studio Berlin in June 2020, once quarantine rules enabled Heras-Casado and Melnikov to reach Germany, and plans had been made to keep everyone 1.5m apart. ‘Simply being in the same room with other musicians, combining sounds again, creating harmony, experiencing rhythm, was very emotional and intense,’ says Queyras. ‘Whether you’re 1m or 1.5m from each other, in the end it doesn’t make such a big difference. It felt almost normal.’ Of course, he points out, it might have been a different story had any one of the concerto’s protagonists ‘not felt so much like family – especially because two days is not much time for such a masterwork. It’s a very dense, demanding piece, particularly for us cellists. But with Isabelle, there is something about the way we both start a phrase, the way we put the bow on the string, the way we breathe, the way we use vibrato and choose our intonation. Our choices go very naturally in the same direction.’

Source: Julien Mignot

Queyras with his c.1696 Gioffredo Cappa cello

Key within their interpretation of the Beethoven is the use of a fortepiano and gut strings, which have an enormous impact on the overall sound colour. ‘The fortepiano is a strong game changer in this combination,’ says Queyras. ‘It’s much more percussive, lighter and more transparent than a modern instrument. And the gut strings give you a crisper attack, but at the same time they are lighter and more supple. They almost always react in an unexpected way, so it puts you on edge. It’s more like playing a living thing than a metal string! Then the strings of the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra can be so biting and rough’ – he accents his ‘r’ and pushes out the rest of the word with a rush of air – ‘in moments when you want it.’

He is keen to dispel the idea that just because the piece is neither solo concerto nor piano trio concerto, but a concerto for three separate instruments, it is somehow inferior to Beethoven’s other works. ‘There has been a lot of talk about the idea that there is “deeper” Beethoven and “lighter” Beethoven, and that the “Triple” Concerto is somehow less existential,’ he says. ‘I disagree strongly. I have a passionate love for this work. If you compare it with late Beethoven, of course, it is a more positive, civil type of music. But the conversation between the soloists and the orchestra means that it doesn’t get superficial at all, and the beauty and depth of it is overwhelming. There are moments which are just absolutely breathtaking.’

In September this year Queyras is due to release a second album, recorded before the pandemic, with Zimmermann, Cologne’s Gürzenich Orchestra and conductor François-Xavier Roth in Strauss’s musical reimagining of Don Quixote, the tale of the mad knight errant and his trusty squire, Sancho Panza. ‘I imagine the young Strauss read Cervantes’ novel and fell in love with this crazy, intriguing guy,’ says Queyras. ‘I really identify myself with this piece and this character.’ Images of Queyras atop an emaciated horse, with missing teeth, a sword, and a barber’s golden basin on his head, with Zimmermann trotting behind on a scruffy ass, flash into my mind. I probe further. ‘I see what you mean,’ he grins. ‘I should take my bow and attack! First of all, I’d like to make a confession: I have a bit of difficulty with Strauss’s tone poems. But Don Quixote is a masterwork in so many ways. The way Strauss works with all the different protagonists, and the way they interact with all the musical elements and themes, is absolutely beyond words. There is so much humanity in this music. The fifth variation, where Don Quixote is awake at night dreaming of Dulcinea, is like an improvised recitative. You feel you are with Don Quixote in his deepest feelings – in his soul.’

Even outside these projects, Queyras’s life is filled with music and creativity. With social distancing measures in place, in July 2020 he ran a downsized version of his French festival Rencontres Musicales de Haute-Provence in Forcalquier. During the pandemic he has also been filming what will be a total of 36 live videos about the Bach Cello Suites, each time finding creative inspiration from a guest instrumentalist, conductor, writer, choreographer, actor and more (see bit.ly/3kaSJey). Apart from this, he has been working with Slovenian composer Vito Žuraj, whose cello concerto he hopes to premiere later this year, and performing with family members including his artist son, who paints as he plays.

Source: Martin bell/Feiburg Baroque Orchestra

Recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto in Berlin

At present, Queyras does not wish to take on anything quite as ambitious as his 2017 Bach Cello Suites project, for which he worked with choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker in dozens of concerts with five dancers (see bit.ly/3jdYsPm) – even though he says, ‘It was better than anything I had dreamed!’ Instead, after exploring world music improvisation with the Chemirani brothers and Sokratis Sinopoulos over the years (see bit.ly/3o4euz7), he now plans to immerse himself in jazz. Twenty years of sporadic work with saxophonist and composer Raphaël Imbert led the two to experiment in 2019 with melding classical and jazz in Invisible Stream (see bit.ly/3m6OWzH), and this year they want to make a CD. ‘It’s a big step for me,’ says Queyras. ‘I never thought I would dare to go more in the direction of jazz. The combination of harmony and improvisation is so complicated! But the life of a musician is a process. Each one of us has to find what is going to keep us alert, alive, inventing. That means taking risks, even if some things that we do are not as good as others.’

Queyras’s collaborations and adventurous nature continually push his personal and musical boundaries. And yet, at the same time, it is these experiences together that form his core as a musician. In many ways, his work with composers and creative musicians today is not so far removed from his performances even of classical works, because it has helped him to interpret their language, and to meld that with his own in the present. ‘When you take a piece of Beethoven that has been played millions of times, I think the way to propose an interpretation that is relevant, alive and that really makes sense in this moment is by going deep into the score, as you would for Ligeti or Boulez, and letting it impregnate you,’ he says. ‘That way, when we play Haydn, or Bach, or Beethoven, we can make these works sound as contemporary as they were when they were created.’

-

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

Read more playing content here